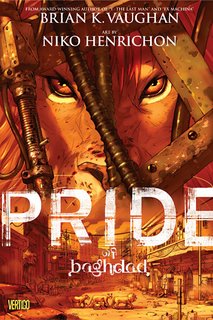

I’m not quite sure what to make of Brian K. Vaughan these days. He certainly caught my, and everyone else’s, attention with Y The Last Man, which remains one of my favourite books. But a stellar first issue of Ex Machina was followed by a fairly dull opening arc that led to my dropping the book, and I’ve never been quite hooked on his superhero work. Even Y has slipped a bit from its once-lofty heights, as Vaughan’s quirks – his style of dialogue, the pop culture references, the flashback origin issues – became repetitive. He’s still good, but one could be forgiven for wondering if he’d reached the edge of his range, or perhaps was just being spread too thin. But when Pride of Baghdad was announced a year ago, I was still excited – the story of a pride of lions who escape from the Baghdad Zoo during American bombings was both compelling in its own right and an interesting departure for Vaughan. I’d never heard of the artist, Nico Henrichon, but that seemed less important – even though Vaughan has lost some of his shine, his work still carries an automatic “Try me!” label. And that’s quite an effective label when the work in question is a hardcover original graphic novel. Thankfully, Pride of Baghdad lives up to much of its promise, thanks in part to Vaughan stretching his storytelling legs, but mostly thanks to the work of his previously unknown artistic collaborator.

I’m not quite sure what to make of Brian K. Vaughan these days. He certainly caught my, and everyone else’s, attention with Y The Last Man, which remains one of my favourite books. But a stellar first issue of Ex Machina was followed by a fairly dull opening arc that led to my dropping the book, and I’ve never been quite hooked on his superhero work. Even Y has slipped a bit from its once-lofty heights, as Vaughan’s quirks – his style of dialogue, the pop culture references, the flashback origin issues – became repetitive. He’s still good, but one could be forgiven for wondering if he’d reached the edge of his range, or perhaps was just being spread too thin. But when Pride of Baghdad was announced a year ago, I was still excited – the story of a pride of lions who escape from the Baghdad Zoo during American bombings was both compelling in its own right and an interesting departure for Vaughan. I’d never heard of the artist, Nico Henrichon, but that seemed less important – even though Vaughan has lost some of his shine, his work still carries an automatic “Try me!” label. And that’s quite an effective label when the work in question is a hardcover original graphic novel. Thankfully, Pride of Baghdad lives up to much of its promise, thanks in part to Vaughan stretching his storytelling legs, but mostly thanks to the work of his previously unknown artistic collaborator.

The story is a departure for Vaughan, whose work is often peppered with pop culture references and historical anecdotes. Writing about animals clearly doesn’t lend itself to Shakespeare jokes, and the history lessons are kept to a bare minimum. The lions are written with human traits, but still maintain animal sensibilities. He’s done at least the bare minimum of research on the species: Zill, the male, is fairly passive and laid back, if not actually lazy, letting the feisty females, Noor and Safa, do most of the hunting and fighting. Vaughan trip slightly into cliché with the cub, Ali, who is innocent, easily impressed, and curious about the world outside the pen he’s known for his entire life. The lions are largely defined by their experiences in the outside world, from Safa’s world-weary knowledge that it wasn’t a bed of roses down to Ali’s fanciful imagination, fed by Zill and Noor’s vague, rose-tinted memories. They aren’t the deepest characters, but they drive the story effectively.

It’s difficult to write a book about the war in Iraq without discussing the political elements, and Vaughan certainly isn’t a writer to shy away from the subject. The politics of Pride of Baghdad are allegorical, easy enough to ignore but there for examination if you’re so inclined: The animals of the zoo represent the Iraqi people under Saddam, caged and restrained if generally well-fed. Despite Noor’s attempts to unite the animals and organize an escape, no one trusts another, and when the US invasion finally sets everyone loose, that mistrust turns to chaos and violence. Even after being imprisoned, the lions can’t bring themselves to see their former captors as potential food, and they find other animals that have taken advantage of their situations as pets. It’s a subtle enough analogy, more Watership Down than Animal Farm, and the only hiccup comes when Vaughan tries to be a little too clever (or perhaps just cute) and has one animal mention an regime change.

Otherwise, Vaughan’s usual traits are all on hand: The dialogue is snappy and clever, and funny when it needs to be, with Ali expressing the desire for other animals his age because he’s always wanted to kill a baby goat. It’s still a very smart script, paring down some of his clever-for-the-sake-of-clever mannerisms due to the necessities of the story. And it’s not hard to imagine early drafts of the script that envisioned the story as a miniseries, with a few of Vaughan’s usual jaw-dropping cliffhanger pages in evidence.

Those moments come courtesy of Nico Henrichon, who steals the spotlight from his higher-billed writer with some astonishing art. I’ve never seen his work before, but he’s certainly jumped onto my must-watch list with Pride, for which he provided pencils, inks, and colours. There’s a rough, sketchy quality to his art, particularly the characters, but it fits together to form a beautiful whole. There’s a distinct European influence on his work (perhaps unsurprising, as he lives in Quebec City), with the slightly rough characters balanced out be intricate backgrounds and incredible colours. Like Vaughan, he treads a fine line between giving the lions distinctive personalities and emotions without veering too far into Disneyfication. Action may be the weakest card in Henrichon’s deck, but it’s nothing to complain about, and only seems weaker due to the exceptional job he does with characterization, setting, and mood.

It’s unusual to buy a Brian K. Vaughan book and come away more impressed with the art than the story, and that’s no small thing given some of the great artists with whom he’s worked. The story he’s written for Pride of Baghdad is good, but not quite great: It’s effectively a simple story, though it can mean a great deal more, which leaves a great deal in the hands of the artist. If entrusted to a lesser artist, the book could have been sappy, trite, and overwrought, but Henrichon’s touch elevates it by several notches. Vaughan isn’t quite able to distance himself from his other, human-based work, but most of the flaws with the script and story are washed away by Henrichon’s wonderful visuals. Vaughan sets up the story and the characters, but Henrichon sells it, and makes Pride of Baghdad one of the most satisfying and affecting books of the year.